Scientists aim towards designing experiments that can give a “true value” from their measurements, but due to the limited precision in measuring devices, they often quote their results with some form of uncertainty.

- Random errors are caused by:

- the readability of the measuring instrument

- the effects of changes in the surrounding such as temperature variations and air currents.

- insufficient data

- the observer misinterpreting the reading.

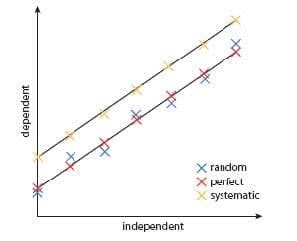

- Random errors make a measurement less precise, but not in any particular direction. They are expressed as an uncertainty range, such as $\rm 25.05 \pm 0.05~°C$.

- The uncertainty of an analogue scale is $\pm$ (half the smallest division).

- The uncertainty of a digital scale is $\pm$ (the smallest scale division).

- Systematic errors occur when there is an error in the experimental procedure.:

For example:- measuring the volume of water from the top of the meniscus rather than the bottom,

- heat loss due to insufficient insulation in thermal experiments another.

- Experiments are repeatable if the same person duplicates the experiment with the same results.

- Experiments are reproducible if several experimentalists duplicate the results.

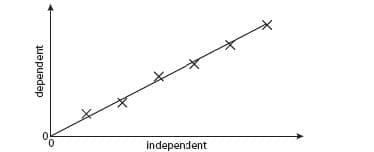

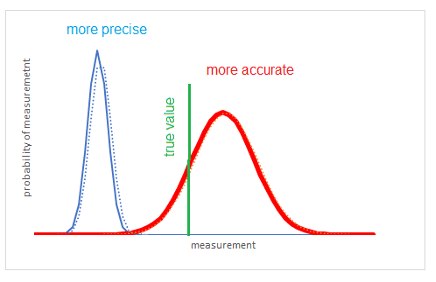

- The precision or reliability of an experiment is a measure of the random error. If the precision is high, then the random error is small.

- The accuracy of a result is a measure of how close the result is to some accepted or literature value If an experiment is accurate then the systematic error is very small.

- Random uncertainties can be reduced by repeating readings; systematic errors cannot be reduced by repeating measurements.

- Precise measurements have small random errors and are reproducible in repeated trials. Accurate measurements have small systematic errors and give a result close to the accepted value.

- If one uncertainty is much larger than others, the approximate uncertainty in the calculated result can be taken as due to that quantity alone.

- The experimental error in a result is the difference between the recorded value and the generally accepted or literature value.

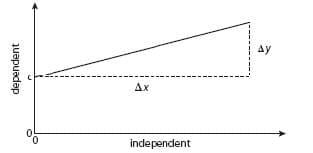

- Percentage uncertainty $=$ (absolute uncertainty /measured value) $\times$ $100\%$

- Percentage error $=$ ((accepted value – experimental value)/ accepted value) $\times$ $100\%$

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA