Key organic reaction types include nucleophilic substitution, electrophilic addition, electrophilic substitution, and redox reactions. Reaction mechanisms vary and help in understanding the different types of reaction taking place.

Nucleophilic substitution reactions between halogenoalkanes: $\bf RX + NaOH$.

- A nucleophile, such as water or hydroxide anion, is a species that can donate a lone electron pair to a positively charged or electron-deficient carbon atom.

- A leaving group is the ion or molecule that detaches from the substrate via a heterolytic bond fission.

- Protic solvents, such as water and alcohols, readily donate protons $\rm (H^+ ions)$ to nucleophiles or form hydrogen bonds with electron-rich species.

- Aprotic solvents, such as ethers, esters and ketones, cannot donate protons $\rm (H^+ ions)$ to other species.

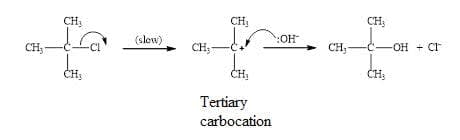

- $\bf S_N1~ mechanism$ $\rm = Substitution~ reaction$, Nucleophilic, Unimolecular.

This is a two step process:

The rate determining involves the heterolytic fission of the $\rm C–X$ bond and the formation of carbocation intermediate. The mechanism is unimolecular as only one species is involved.

The $\rm OH^-$ nucleophile than attacks the carbo cation in the second step.

Note curly arrows in mechanisms show the movement of electron pairs.

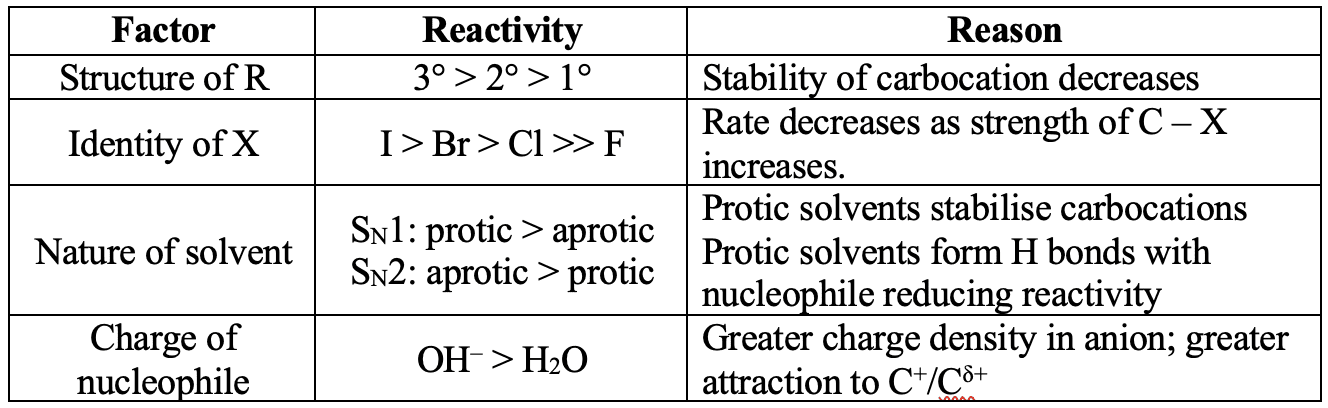

Favoured by tertiary halogenoalkanes due to stability of the tertiary carbocation. Carried out in protic polar solvents. - $\bf S_N2~ mechanism$ $\rm = substitution~reaction$, Nucleophilic, Bimolecular.

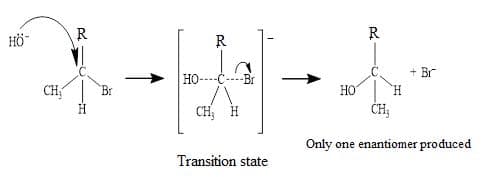

This is one step process and proceeds via a transition state with carbon partially bonded to the $\rm X$ leaving group and the nucleophile.

The reaction is stereospecific: with one optical isomers or enantiomers of a compound, produced but not the other.

It is carried out in aprotic, polar solvents. - $\rm OH^–$ is a stronger nucleophile than $\rm H_2O$ as it has a negative charge, in addition to lone pairs.

- Tertiary halogenoalkanes in protic solvents readily form tertiary carbocations, so they produce alcohols via the unimolecular $\rm S_N1$ mechanism.

- Primary carbocations are unstable, so primary halogenoalkanes undergo hydrolysis via the $\rm S_N2$ mechanism, usually in a polar aprotic solvents.

- Secondary halogenoalkanes can participate in both $\rm S_N1$ and $\rm S_N2$ reactions, which often proceed in parallel to each other.

Factors affecting the reactivity of halogenoalkanes $\bf (R- X)$

Electrophilic addition reactions: Alkene $\bf + Br_2 / XY$ interhalogens / $\bf HX$

- The $\pi$ bond in alkenes has a high electron-density and attracts electrophiles.

- Electrophiles are electron-deficient species, generated by heterolytic fission:

$\rm e.g. H^+$ from $\rm HBr$ or $\rm Br^+$ from $\rm Br_2$. - Electrophilic addition reactions involve breaking the $\pi$ bond of the double bond, creating two new bonding positions for the addition product.

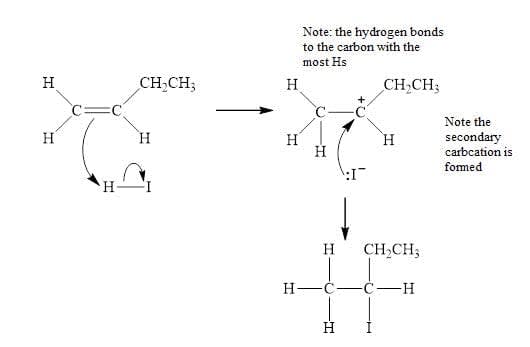

- Unsymmetrical alkenes can form two carbocations that differ in their stability. The more stable cation $(3° > 2° > 1°)$ is formed preferentially and gives the main reaction product.

- This explains Markovnikov’s rule:

The halide component of HX bonds preferentially at the more highly substituted carbon, whereas the hydrogen (more generally the least electronegative element) prefers the carbon which already contains the most hydrogen.

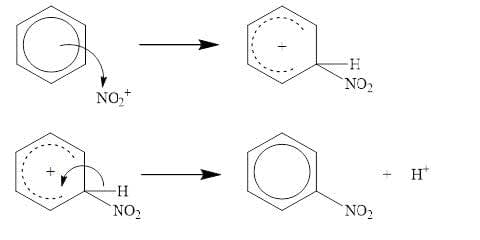

Electrophilic substitution reactions: $\bf Benzene + HNO_3/H_2SO_4$

- The delocalized ring of $\pi$ electrons in benzene is an electron-dense area, to which electrophiles are attracted.

- Substitution reactions in benzene involve the replacement of a hydrogen atom in the benzene ring by an electrophile. This preserves the stability of the benzene ring structure.

- Nitration of benzene uses a nitrating mixture of the concentrated acids $\rm HNO_3$ and $\rm H_2SO_4$, which generates the electrophile $\rm NO_2^+$ that substitutes in benzene.

$\rm H_2SO_4 + HNO_3 \rightarrow HSO_4^– + H_2NO_3^+$

$\rm H_2NO_3^+ \rightarrow H_2O + NO_2^+$

Reduction reactions

- These are often defined in terms of gain of $\rm H$/loss of $\rm O$ in organic chemistry.

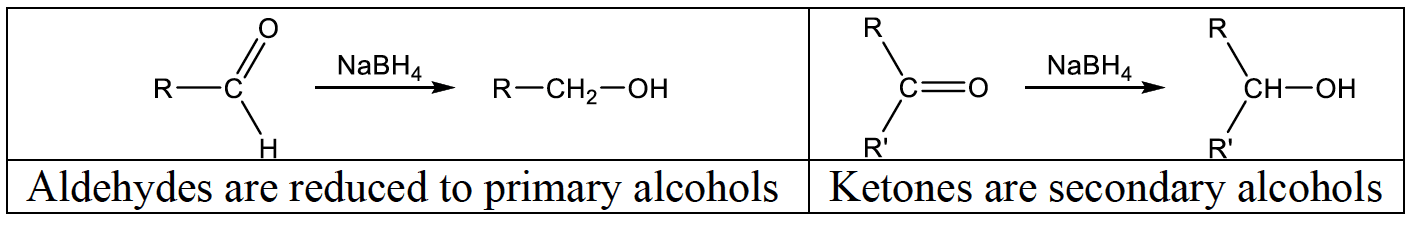

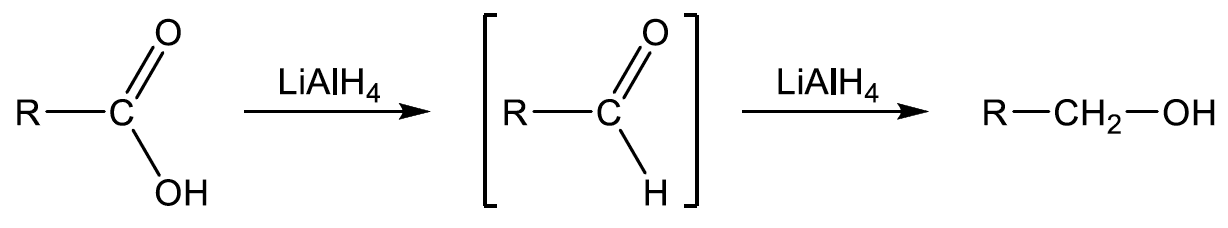

- Reducing agents for carbonyl compounds are $\rm NaBH_4$ or $\rm LiAlH_4$, which both produce $\rm H^–$ ions which are nucleophiles which attach the partially positive charged $\rm C$ in the $\rm C = O$ group:

- aldehydes are reduced to primary alcohols and ketones are reduced to secondary alcohols with $\rm NaBH_4$.

- carboxylic acids are reduced to aldehydes with the powerful reducing agent $\rm LiAlH_4$:

- aldehydes are reduced to primary alcohols and ketones are reduced to secondary alcohols with $\rm NaBH_4$.

- Reducing agents for nitrobenzene are $\rm Sn$ and conc. $\rm HCl$. Nitrobenzene is reduced to phenylammonium ions:

$\rm C_6H_5NO_2(l) + 3Sn(s) + 7HCl(aq)$ $\rm \rightarrow [C_6H_5NH_3]^+ Cl^–(aq)$ $+$ $\rm 3SnCl2(aq) + 2H_2O(l)$ and the addition of $\rm NaOH(aq)$ produces phenylamine:

$\rm [C_6H_5NH_3]^+Cl^–(aq) + NaOH(aq)$ $\rm \rightarrow C_6H_5NH_2(l) + NaCl(aq) + H_2O(l)$ - Nitrobenzene can also be reduced with hydrogen gas with a $\rm Ni$ or $\rm Pt$ catalyst at high pressure and temperature: $\rm C_6H_5NO_2(l) + 3H_2(g)$ $\rm \rightarrow C_6H_5NH_2(l) + 2H_2O(l)$

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA