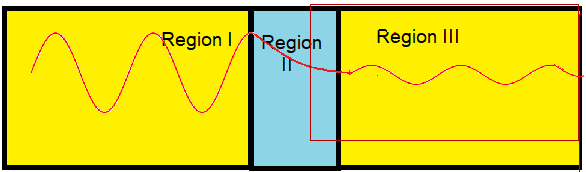

The microscopic quantum world behaves in a way that cannot be understood in terms of the macroscopic world of the ideas of the classical world based on our everyday experience. New ideas and concepts are needed.

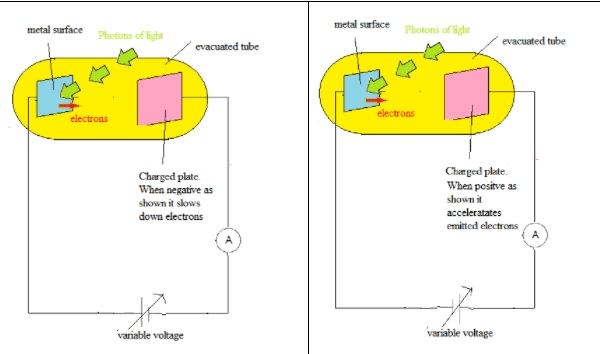

- Electrons are emitted from a metal surface when electromagnetic radiation is incident on the surface.

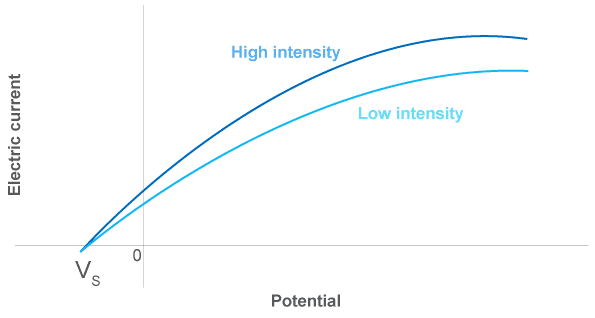

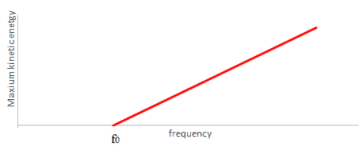

- The kinetic energy of the emitted electrons $(\mathrm E_k)$ depends on the frequency of light. In classical theory the energy of the incident light waves depends on the intensity of light not the frequency.

- The light intensity only affects the number of electrons emitted (i.e. the photocurrent).

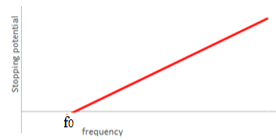

- There is a threshold frequency $\bf (\boldsymbol{f}_0)$ below which no electrons are emitted. In classical theory electrons would be emitted at all frequencies if the intensity was sufficiently high.

From Einstein' explanation below:

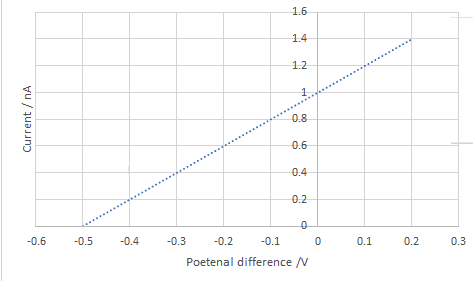

$\mathrm E_{k}=h f-\varphi$

$\mathrm E_{k} = hf - hf_0$

$h$ can be determined from the gradient.

The work function $(\varphi)$ can be determined from the horizontal intercept $f_{0}$.

$\varphi = h f_0$

$\mathrm E_k = hf - hf_0$ - Electrons are emitted with essentially no time delay. In classical theory it would take time for the electrons to collect the necessary threshold energy from the incident waves to escape.

- These facts are in contradiction with the classical wave theory of radiation and canonly be understood if light is considered to be a stream of particles called photons.

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA