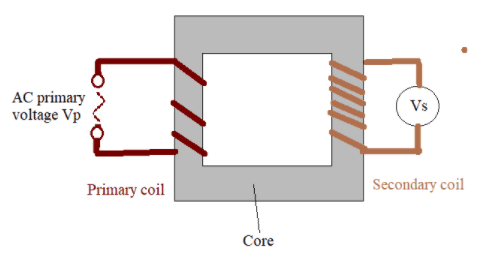

Alternating current $(ac)$ electricity is the most convenient to generate, transform and transmit.

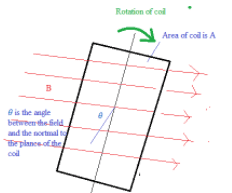

- Electricity for commercial and home use comes mainly from generators that involve a coil rotating in a magnetic field.

$\Phi=\mathrm{BA} \cos \theta$

If $\omega$ is angular frequency, $\theta=\omega t$

$\Phi=\mathrm{BA} \cos \omega \mathrm{t}$

$\varepsilon=-\Delta \Phi / \Delta \mathrm{t}=\omega \mathrm{BA} \sin \omega \mathrm{t}$ - This shows:

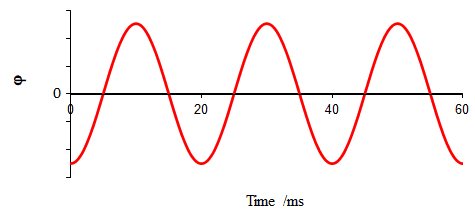

- The flux, and emf oscillate with the same frequency

- The flux and the voltage are out of phase by $\pi/2$

- The induced emf is proportional to the angular frequency. If angular frequency is doubled the peak voltage is also doubled.

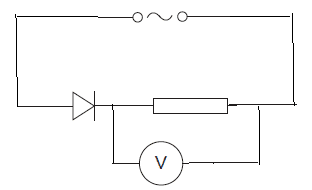

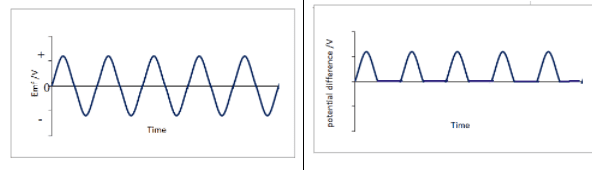

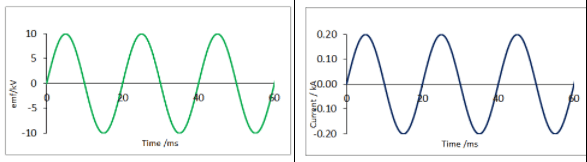

- In the example below, the coil rotates with a period of $\rm 20~ms$.

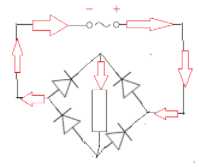

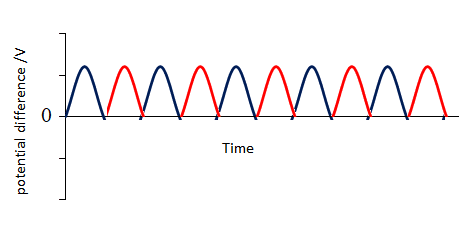

- The corresponding induced emf and current in a domestic supply are shown below.

- The following should be noted:

- The flux, emf and current oscillate with the same frequency.

- The current and the voltage are in phase

- When the flux is zero the rate of change of flux has maximum magnitude and so has the emf and current.

- When the flux has maximum magnitude the rate of change of flux is zero and so is the emf and current.

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA