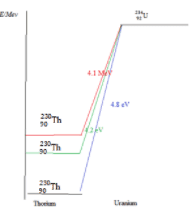

The nucleus occupies discrete energy levels like the electron.

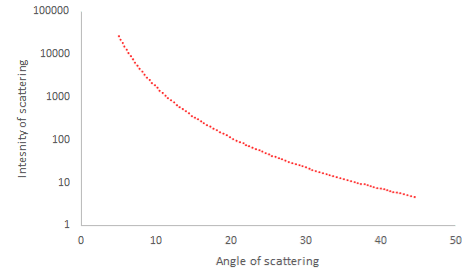

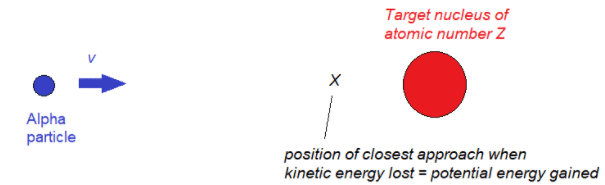

- Evidence of the size of the nucleus can be obtained by firing alpha particles at a nucleus

- For a given speed of an alpha particle, the closest approach to a nucleus, $r_{\min}$ will occur when the initial kinetic energy has been converted into electric potential energy.

Kinetic energy lost $=½~ m v^{2}$

Potential energy gained $=\mathrm Q q / 4 \pi \epsilon_{a} r$

$\mathrm{Q}$ is the charge of target nuclei $\mathrm{Ze}$ and $q$ is the charge of an alpha particle $=2 \mathrm{e}$

Potential energy gained $\rm =2 e \times Z e / 4 \pi \epsilon_{o} \mathcal r$ $=\rm Z e^{2} / 2 \pi \epsilon_{o} \mathcal r$

At the position of closest approach:

$½~ m v^{2}=\rm Z e^{2} / 2 \pi \epsilon_{o} \mathcal r_{\text {min }}$

$r_{\min }=\rm Ze^{2} / 2 \pi \epsilon_{0} \mathcal{m v}^{2}$

Worked Example

Calculate the diameter of a gold nucleus $\rm (Z=79)$ if an alpha particle with a kinetic energy of $2.0 \mathrm{MeV}$ is scattered backwards.

Solution

$\rm E_{k}=2.0 \times 10^{6} \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19} ~J$

$m v^{2}=2 \times 2.0 \times 10^{6} \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{~J}$ $=4.0 \times 10^{6} \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \mathrm{~J}$

$r_{\min }= 79 \times(1.6 \times 10^{-19})^{2} /(2 \pi \times 8.85$ $\times$ $10^{-12} \times 4.0 \times 10^{6} \times~ 1.6 ~\times~ 10^{-19}) \mathrm{~J}$

$r_{\min }=5.68282 \times 10^{-14}$

$d=2 \times 5.68282 \times 10^{-14}$

$d=1.1 \times 10^{-13} \mathrm{~m} .$

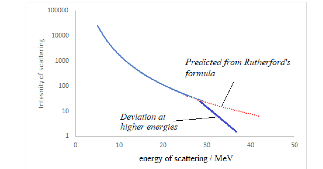

- This distance gives an overestimate for the diameter of a nucleus. It is outside the range of the nuclear force, so the alpha particle is simply repelled by the electrostatic repulsive force.

- If the energy of the incoming particle is increased, the distance of closest approach decreases allowing a better estimate for the nuclear radius.

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA