In the microscopic world energy is discrete. It is carried in packets or quanta.

Spectra

- Light can be considered to be a wave or a particle. Particles of light are called photons.

- The electromagnetic spectrum includes in order of increasing frequency/energy: radio waves, microwaves, IR radiation, visible light, ultraviolet radiation X-rays, and $\gamma$ rays.

- The frequency $(f)$ and wavelength $[\lambda]$ of electromagnetic radiation are related by: $\mathrm{c}$ (speed of light $)=\lambda f$.

- The energy of a photon of light $E_{\text {photon }}$ is related to the frequency $(f)$ of the radiation by Planck's equation:

$\mathrm E_{\text {photon }}=h f= \dfrac{h c}{\lambda}$

$h$ is Planck's constant: $6.63 \times 10^{-34} \mathrm{Js}$ and $c$ is the speed of light $=3.00 \times 10^{8} \mathrm{~m} \mathrm{~s}^{-1}$ - A continuous spectrum contains radiation of all wavelengths within a given range (e.g. the visible spectrum).

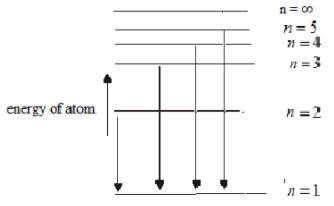

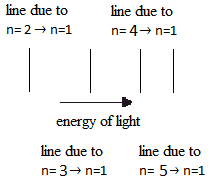

- A line spectrum consists of a mixture of discrete lines of different wavelengths/frequencies.

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA

Nouveau ! Découvrez Nomad'IA : le savoir de nos 400 profs + la magie de l'IA